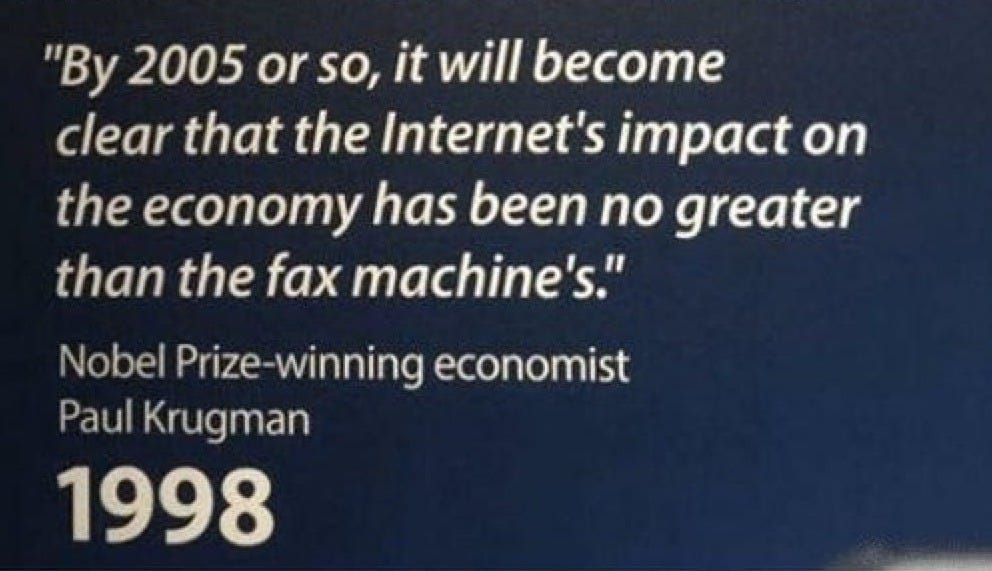

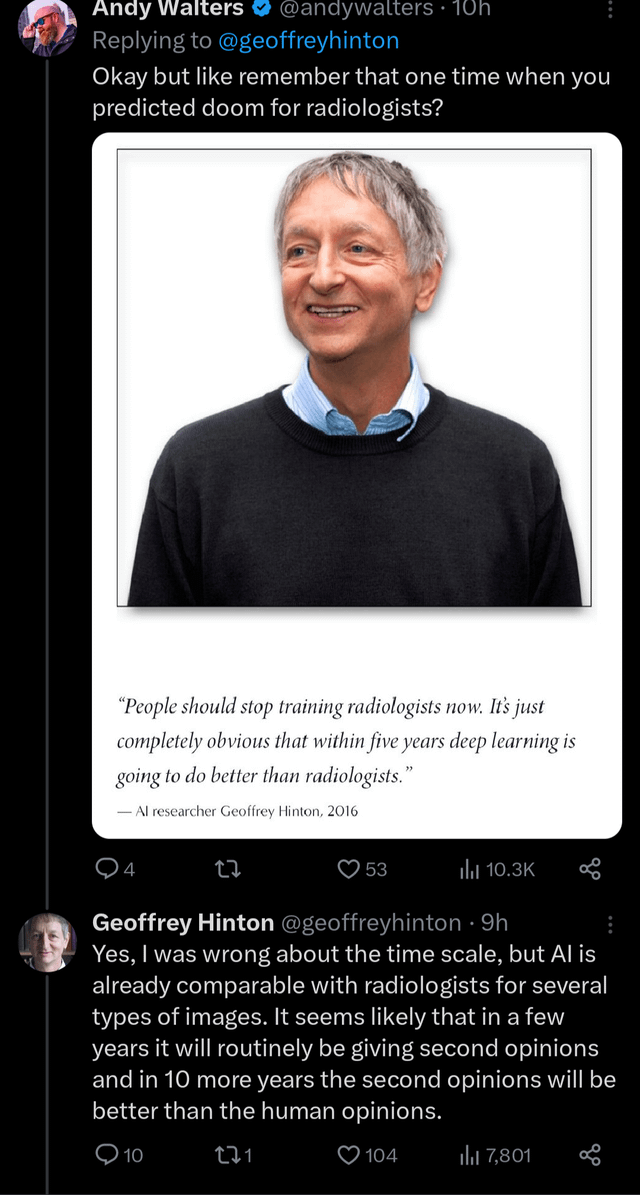

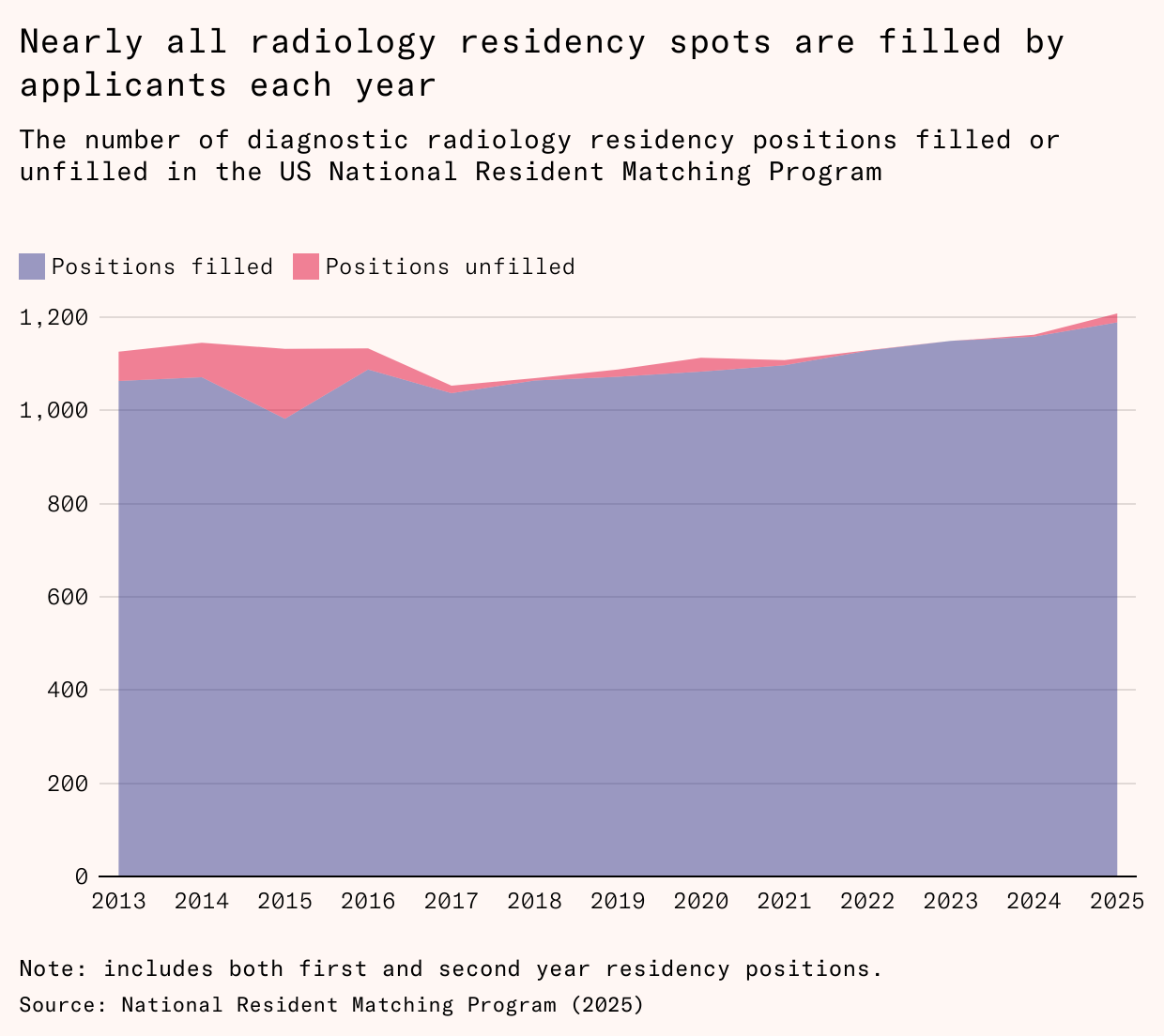

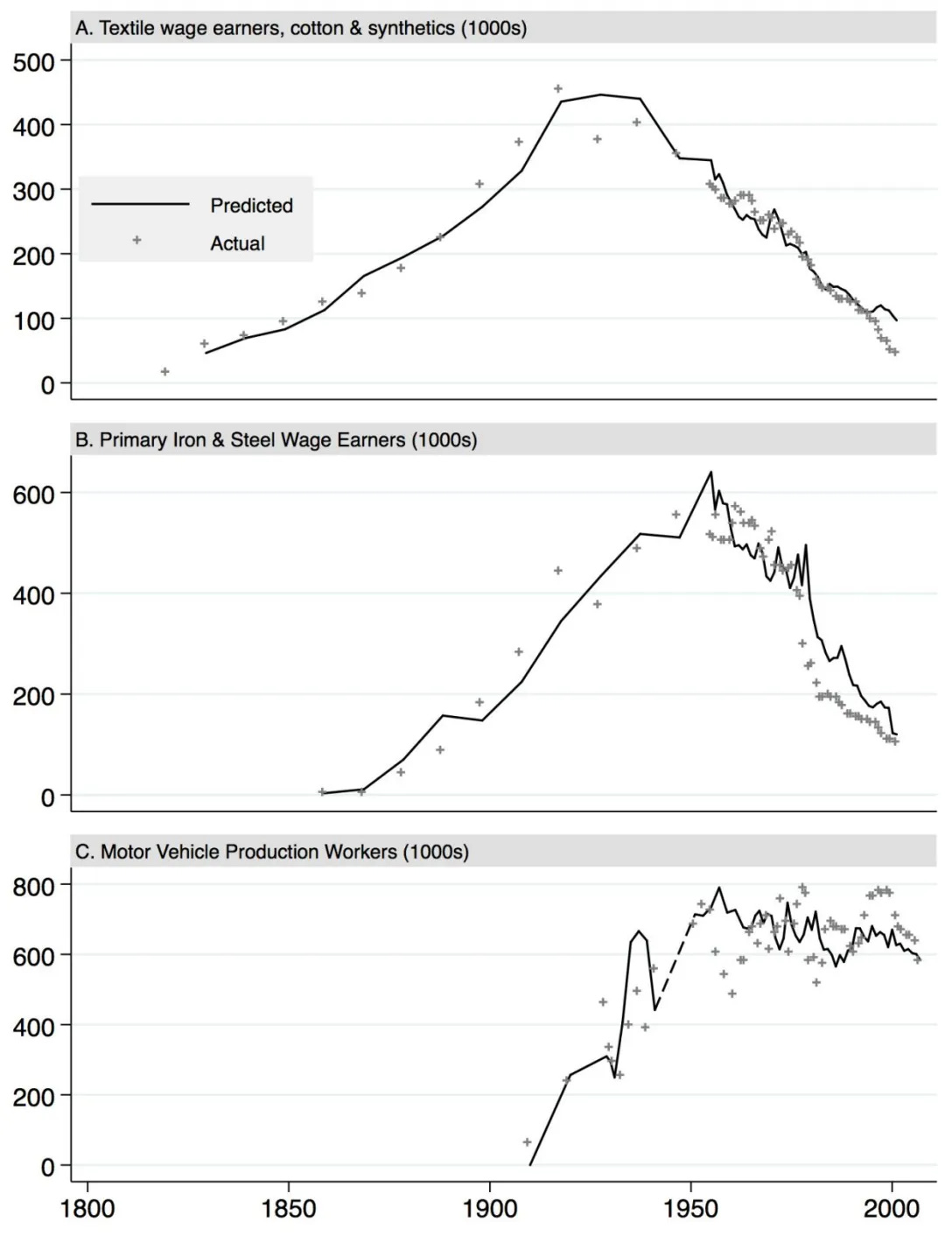

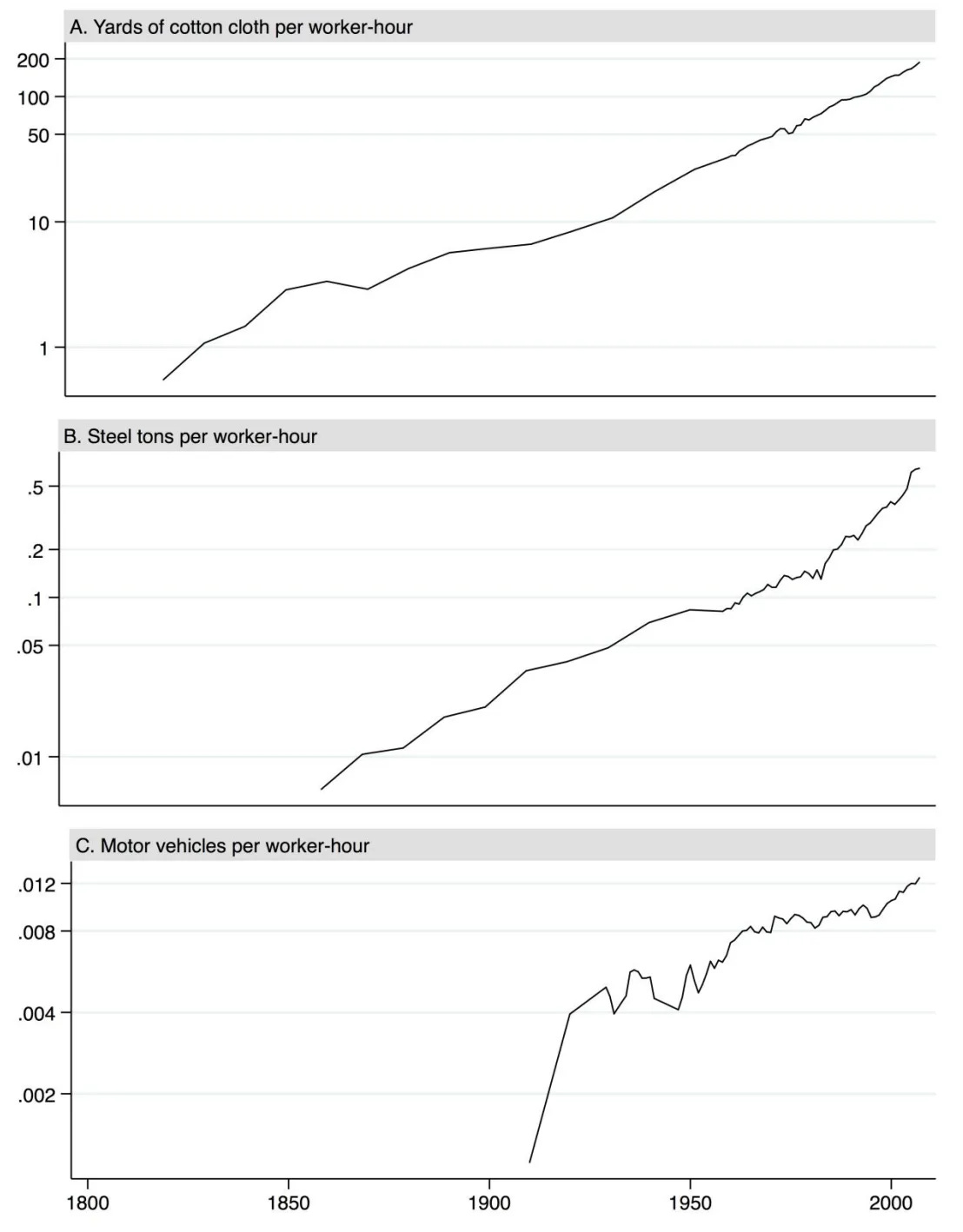

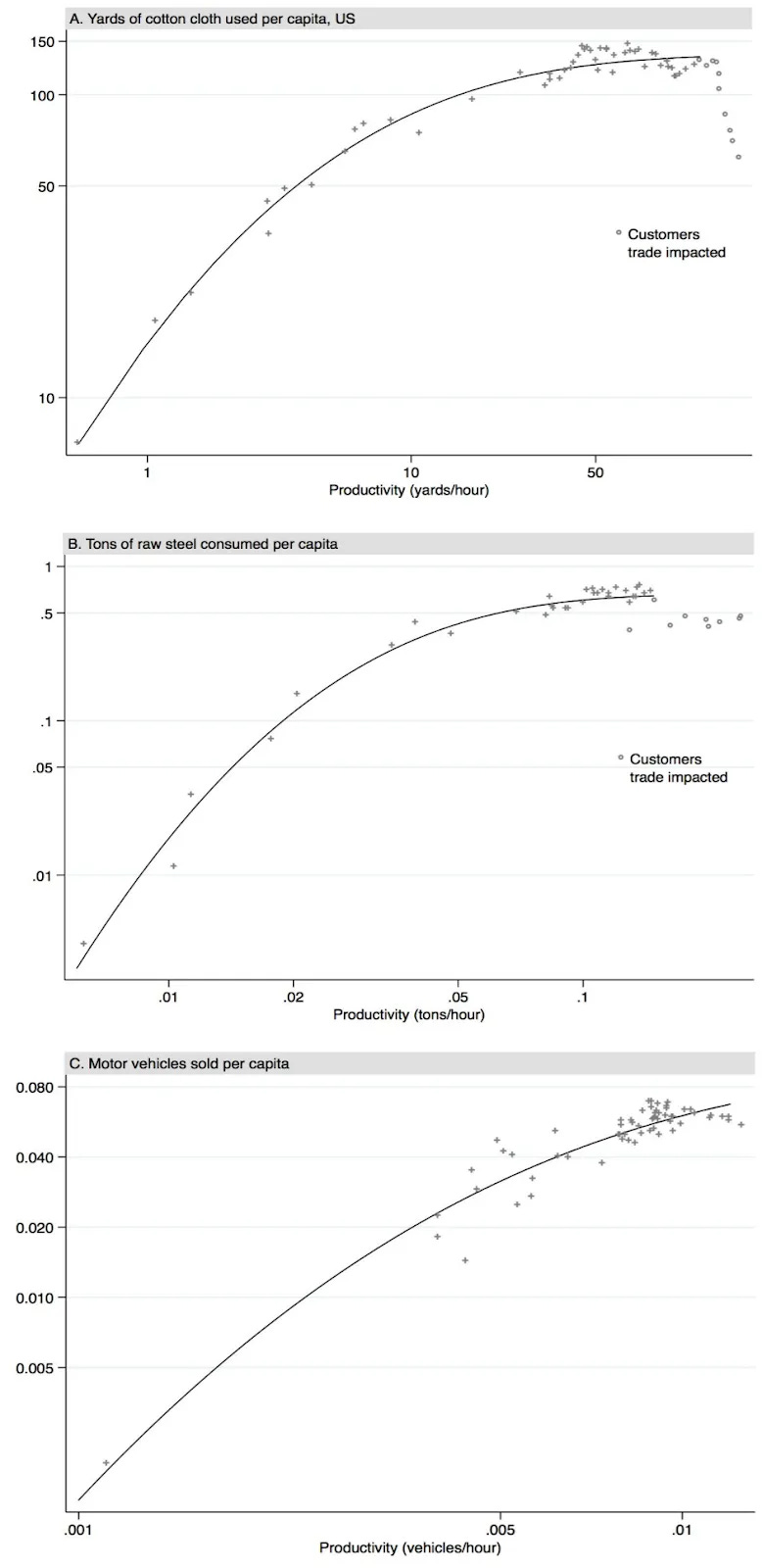

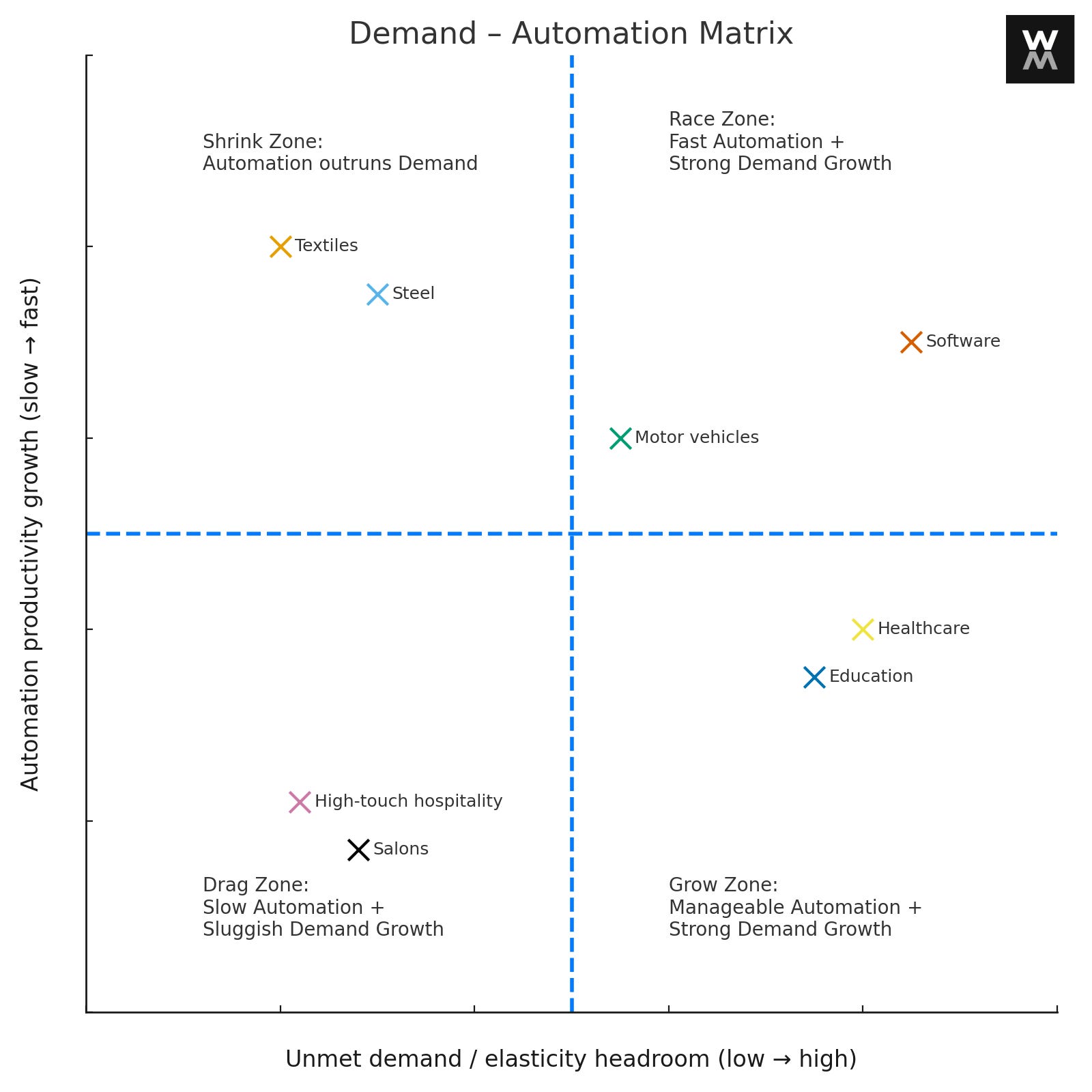

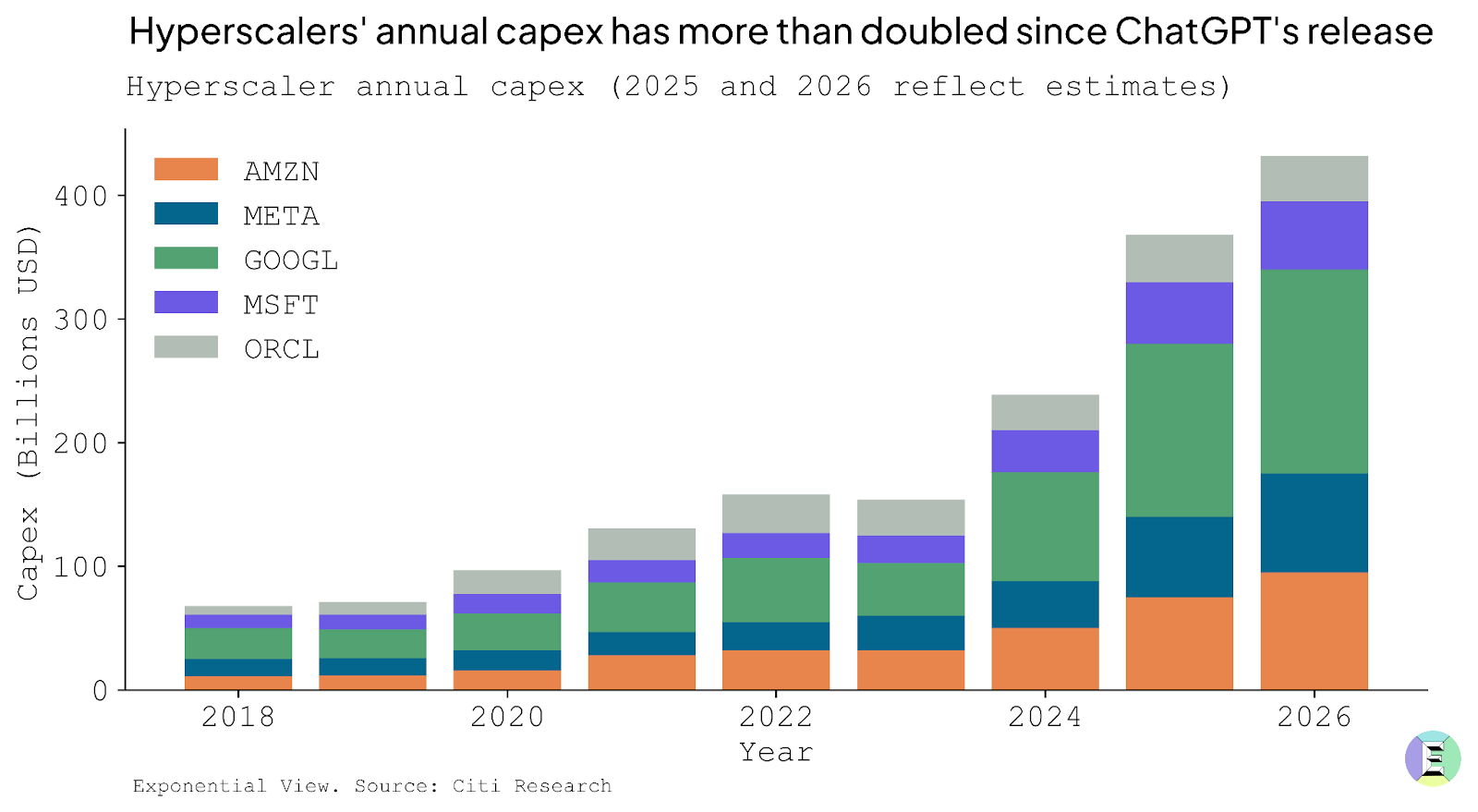

人工智能的拨号上网时代 ylc3000 2025-11-13 0 浏览 0 点赞 长文 AI's Dial-Up Era 人工智能的拨号上网时代 By Nowfal 作者:Nowfal Oct 18, 2025 2025年10月18日 It is 1995. <br> 现在是1995年。 Your computer modem screeches as it tries to connect to something called the internet. Maybe it works. Maybe you try again. <br> 你的电脑调制解调器在尝试连接一个叫做“互联网”的东西时发出刺耳的尖叫声。也许连接成功了。也许你得再试一次。 For the first time in history, you can exchange letters with someone across the world in seconds. Only 2000-something websites exist1, so you could theoretically visit them all over a weekend. Most websites are just text on gray backgrounds with the occasional pixelated image2. Loading times are brutal. A single image takes a minute, a 1-minute video could take hours. Most people do not trust putting their credit cards online. The advice everyone gives: don’t trust strangers on the internet. <br> 历史上第一次,你可以在几秒钟内与世界另一端的人交换信件。当时只有大约2000多个网站存在1,所以理论上你可以在一个周末内访问所有网站。大多数网站只是灰色背景上的文字,偶尔带有一张像素化的图片2。加载时间长得令人发指。一张图片需要一分钟,一个1分钟的视频可能需要几个小时。大多数人不信任在网上输入信用卡信息。大家给出的建议是:不要相信网上的陌生人。 People split into two camps very soon. <br> 人们很快就分成了两个阵营。 Optimists predict grand transformations. Some believe digital commerce will overtake physical retail within years. Others insist we’ll wander around in virtual reality worlds. <br> 乐观主义者预测将发生巨大的变革。一些人相信数字商务将在几年内超越实体零售。另一些人则坚信我们将在虚拟现实世界中漫游。 “I expect that within the next five years more than one in ten people will wear head-mounted computer displays while traveling in buses, trains, and planes.” - Nicholas Negroponte, MIT Professor, 1993 “我预计在未来五年内,超过十分之一的人在乘坐公共汽车、火车和飞机时会佩戴头戴式计算机显示器。” - 尼古拉斯·尼葛洛庞帝,麻省理工学院教授,1993年 Pessimists call the internet a fad and a bubble. <br> 悲观主义者则称互联网为一时的狂热和泡沫。  Source: Did Paul Krugman Say the Internet’s Effect on the World Economy Would Be ‘No Greater Than the Fax Machine’s’? Snopes, 2018. Original quote in Red Herring magazine, 1998 <br> 来源:保罗·克鲁格曼是否说过互联网对世界经济的影响“不会比传真机更大”?Snopes, 2018。原始引文发表于《红鲱鱼》杂志,1998年 If you told the average person in 1995 that within 25 years, we’d consume news from strangers on social media over newspapers, watch shows on-demand in place of cable TV, find romantic partners through apps more than through friends, and flip “don’t trust strangers on the internet” so completely that we’d let internet strangers pick us up in their personal vehicles and sleep in their spare bedrooms, most people would find that hard to believe. <br> 如果你在1995年告诉一个普通人,25年内,我们将通过社交媒体上的陌生人获取新闻而不是报纸,按需观看节目而不是有线电视,通过应用程序寻找伴侣而不是朋友介绍,并且将“不要相信网上的陌生人”这条原则完全颠覆,以至于我们会让网上的陌生人用他们的私家车接我们,并睡在他们空余的卧室里,大多数人会觉得这难以置信。 We’re in 1995 again. This time with Artificial Intelligence. <br> 我们又回到了1995年。这一次是关于人工智能。 And both sides of today’s debate are making similar mistakes. <br> 而今天辩论的双方都在犯类似的错误。 One side warns that AI will eliminate entire professions and cause mass unemployment within a couple of years. The other claims that AI will create more jobs than it destroys. One camp dismisses AI as overhyped vaporware destined for a bubble burst, while the other predicts it will automate every knowledge task and reshape civilization within the decade. <br> 一方警告说,人工智能将在几年内淘汰整个行业并导致大规模失业。另一方则声称人工智能创造的就业机会将多于其摧毁的。一个阵营将人工智能斥为注定要破裂的过度炒作的“空气软件”,而另一个阵营则预测它将在十年内自动化所有知识型任务并重塑文明。 Both are part right and part wrong. <br> 双方都部分正确,也部分错误。 The Employment Paradox: Why Automation’s Impact Depends On The Industry 就业悖论:为什么自动化的影响取决于行业 Geoffrey Hinton, who some call the Father of AI, warned in 2016 that AI would trigger mass unemployment. “People should stop training radiologists now,” he declared, certain that AI would replace them within years. <br> 被称为“人工智能之父”之一的杰弗里·辛顿在2016年警告说,人工智能将引发大规模失业。他宣称:“人们现在应该停止培养放射科医生了,”他确信人工智能将在几年内取代他们。  Source: Twitter/X, Andy Walters/Geoffrey Hinton, 2023 <br> 来源:Twitter/X, Andy Walters/Geoffrey Hinton, 2023年 Yet as Deena Mousa, a researcher, shows in “The Algorithm Will See You Now,” AI hasn’t replaced radiologists, despite predictions. It is thriving. <br> 然而,正如研究员迪娜·穆萨在《算法现在为你诊断》一文中所展示的,尽管有种种预测,人工智能并未取代放射科医生。这个行业反而正在蓬勃发展。 In 2025, American diagnostic radiology residency programs offered a record 1,208 positions across all radiology specialties, a four percent increase from 2024, and the field’s vacancy rates are at all-time highs. In 2025, radiology was the second-highest-paid medical specialty in the country, with an average income of $520,000, over 48 percent higher than the average salary in(https://radiologybusiness.com/topics/healthcare-management/radiologist-salary/average-radiologist-pay-has-leapt-nearly-38-2015#). 2025年,美国诊断放射学住院医师项目在所有放射学专业中提供了创纪录的1208个职位,比2024年增加了4%,该领域的职位空缺率也达到了历史新高。2025年,放射学成为全美收入第二高的医学专业,平均收入为52万美元,比2015年的平均工资高出48%以上。  Source: The algorithm will see you now, Deena Mousa, 2025 <br> 来源:《算法现在为你诊断》,迪娜·穆萨,2025年 Mousa identifies a few factors for why the prediction failed - real-world complexity, the job involves more than image recognition, and regulatory/insurance hurdles. Most critical she points is Jevons Paradox, which is the economic principle that a technological improvement in resource efficiency leads to an increase in the total consumption of that resource, rather than a decrease. Her argument is that as AI makes radiologists more productive, better diagnostics and faster turnaround at lower costs mean more people get scans. So employment doesn’t decrease. It increases. <br> 穆萨指出了预测失败的几个因素——现实世界的复杂性、工作涉及的不仅仅是图像识别,以及监管/保险方面的障碍。她指出的最关键的一点是杰文斯悖论,即***一项技术提高资源效率的经济原则,会导致该资源总消耗量的增加,而不是减少。***她的论点是,随着人工智能使放射科医生更有效率,更优的诊断和更快的周转时间以更低的成本意味着更多的人会进行扫描。因此,就业没有减少,反而增加了。 This is also the Tech world’s consensus. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella agrees, as does Box CEO Aaron Levie, who suggests: <br> 这也是科技界的共识。微软CEO萨蒂亚·纳德拉同意这一点,Box CEO亚伦·莱维也表示: “The least understood yet most important concept in the world is Jevons Paradox. When we make a technology more efficient, demand goes well beyond the original level. AI is the perfect example of this—almost anything that AI is applied to will see more demand, not less.” “世界上最不被理解但最重要的概念是杰文斯悖论。当我们让一项技术更有效率时,需求会远远超过原来的水平。人工智能就是这方面的一个完美例子——几乎所有应用人工智能的领域都会看到更多的需求,而不是更少。” They’re only half right. <br> 他们只说对了一半。 First, as Andrej Karpathy, the computer scientist who coined the term vibe coding, points out, radiology is not the right job to look for initial job displacements. <br> 首先,正如创造了“氛围编程”一词的计算机科学家安德烈·卡帕西所指出的,放射学并不是寻找初期工作岗位替代的合适领域。 “Radiology is too multi-faceted, too high risk, too regulated. When looking for jobs that will change a lot due to AI on shorter time scales, I’d look in other places - jobs that look like repetition of one rote task, each task being relatively independent, closed (not requiring too much context), short (in time), forgiving (the cost of mistake is low), and of course automatable giving current (and digital) capability. Even then, I’d expect to see AI adopted as a tool at first, where jobs change and refactor (e.g. more monitoring or supervising than manual doing, etc).” “放射学太复杂、风险太高、监管太严。在寻找短期内会因人工智能而发生巨大变化的职位时,我会去别的地方找——那些看起来像重复单一死记硬背任务的职位,每个任务相对独立、封闭(不需要太多背景信息)、耗时短、容错率高(犯错成本低),当然还有在当前(和数字化)能力下可自动化的职位。即便如此,我预计最初人工智能会被用作工具,工作会发生变化和重构(例如,更多的是监控或监督,而不是手动操作等)。” Second, the tech consensus that we will see increased employment actually depends on the industry. Specifically, how much unfulfilled demand can be unlocked in that industry, and whether this unfulfilled demand growth outpaces continued automation and productivity improvement. <br> 其次,科技界关于就业会增加的共识实际上取决于行业。具体来说,取决于该行业能释放出多少未被满足的需求,以及这种未被满足的需求增长是否超过了持续的自动化和生产力提升。 To understand this better, look at what actually happened in three industries over a 200-year period from 1800 to 2000. In the paper Automation and jobs: when technology boosts employment, James Bessen, an economist, shows the employment, productivity, and demand data for textile, iron & steel, and motor vehicle industries. <br> 为了更好地理解这一点,我们来看看从1800年到2000年这200年间三个行业的实际情况。经济学家詹姆斯·贝森在其论文《自动化与就业:当技术促进就业时》中,展示了纺织、钢铁和汽车行业的就业、生产力和需求数据。  Source: Automation and jobs: when technology boosts employment, James Bessen, 2019 <br> 来源:《自动化与就业:当技术促进就业时》,詹姆斯·贝森,2019年 After automation, both textile and iron/steel workers saw employment increase for nearly a century before experiencing a steep decline. Vehicle manufacturing, by contrast, holds steady and hasn’t seen the same steep decline yet. <br> 自动化之后,纺织和钢铁行业的工人在将近一个世纪的时间里就业率有所增长,之后才出现急剧下降。相比之下,汽车制造业则保持稳定,尚未出现同样急剧的下降。 To answer why those two industries saw sharp declines but motor vehicle manufacturing did not, first look at the productivity of workers in all three industries: <br> 要回答为什么这两个行业出现急剧下滑而汽车制造业没有,首先要看这三个行业工人的生产力:  Source: Automation and jobs: when technology boosts employment, James Bessen, 2019 <br> 来源:《自动化与就业:当技术促进就业时》,詹姆斯·贝森,2019年 Then look at the demand across those three industries: <br> 然后看看这三个行业的需求情况:  Source: Automation and jobs: when technology boosts employment, James Bessen, 2019 <br> 来源:《自动化与就业:当技术促进就业时》,詹姆斯·贝森,2019年 What the graphs show is a consistent pattern (note: the productivity and demand graphs are logarithmic, meaning productivity and demand grew exponentially). Early on, a service or product is expensive because many workers are needed to produce it. Most people can’t afford it or use them sparingly. For example, in the early 1800s, most people could only afford a pair of pants or shirt. Then automation makes workers dramatically more productive. A textile worker in 1900 could produce fifty times more than one in 1800. This productivity explosion crashes prices, which creates massive new demand. Suddenly everyone can afford multiple outfits instead of just one or two. Employment and productivity both surge (note: employment growth masks internal segment displacement and wage changes. See footnote3) <br> 图表显示了一个一致的模式(注意:生产力和需求图表是对数尺度的,意味着生产力和需求呈指数级增长)。早期,由于需要大量工人生产,服务或产品价格昂贵。大多数人买不起或很少使用它们。例如,在19世纪初,大多数人只能买得起一条裤子或一件衬衫。然后,自动化使工人的生产力大幅提高。1900年的一名纺织工人比1800年的一名工人能多生产五十倍的产品。这种生产力爆炸导致价格暴跌,从而创造了巨大的新需求。突然之间,每个人都能买得起多套服装,而不仅仅是一两套。就业和生产力双双飙升(注意:就业增长掩盖了内部细分市场的岗位转移和工资变化。见脚注3)。 Once demand saturates, employment doesn’t further increase but holds steady at peak demand. But as automation continues and workers keep getting more productive, employment starts to decline. In textiles, mechanization enabled massive output growth but ultimately displaced workers once consumption plateaued while automation and productivity continued climbing. We probably don’t need infinite clothing. Similarly, patients will likely never need a million radiology reports, no matter how cheap they become and so radiologists will eventually hit a ceiling. We don’t need infinite food, clothing, tax returns, and so on. <br> 一旦需求饱和,就业便不再进一步增加,而是稳定在需求高峰期。但随着自动化持续进行,工人生产力不断提高,就业开始下降。在纺织业,机械化实现了巨大的产量增长,但一旦消费达到平台期,而自动化和生产力继续攀升,工人最终被取代。我们可能不需要无限的衣物。同样,无论放射学报告变得多便宜,患者可能永远不需要一百万份报告,因此放射科医生最终会达到一个上限。我们不需要无限的食物、衣物、报税单等等。 Motor vehicles, in Bessen’s graphs, tell a different story because demand remains far from saturated. Most people globally still don’t own cars. Automation hasn’t completely conquered manufacturing either (Tesla’s retreat from full manufacturing automation proves the current technical limits). When both demand and automation potential remain high, employment can sustain or even grow despite productivity gains. <br> 在贝森的图表中,汽车行业则讲述了一个不同的故事,因为需求远未饱和。全球大多数人仍然没有汽车。自动化也尚未完全征服制造业(特斯拉从完全制造业自动化中退却就证明了当前的技术局限性)。当需求和自动化潜力都保持高位时,尽管生产力有所提高,就业仍能维持甚至增长。 Software presents an even more interesting question. How many apps do you need? What about software that generates applications on demand, that creates entire software ecosystems autonomously? Until now, handcrafted software was the constraint. Expensive software engineers and their our labor costs limited what companies could afford to build. Automation changes this equation by making those engineers far more productive. Both consumer and enterprise software markets suggest significant unmet demand because businesses have consistently left projects unbuilt4. They couldn’t justify the development costs or had to allocate limited resources to their top priority projects. I saw this firsthand at Amazon. Thousands of ideas went unfunded not because they lacked business value, but because of the lack of engineering resources to build them. If AI can produce software at a fraction of the cost, that unleashes enormous latent demand. The key question then is if and when that demand will saturate. <br> 软件则提出了一个更有趣的问题。你需要多少个应用程序?那些可以按需生成应用程序,自主创建整个软件生态系统的软件呢?到目前为止,手工制作的软件是制约因素。昂贵的软件工程师和他们的我们的劳动力成本限制了公司能够负担得起的开发项目。自动化通过使这些工程师的生产力大幅提高来改变这一等式。消费者和企业软件市场都表明存在巨大的未满足需求,因为企业一直有项目未开发4。他们无法证明开发成本的合理性,或者不得不将有限的资源分配给他们的最高优先级项目。我在亚马逊亲眼目睹了这一点。成千上万的想法没有得到资助,不是因为它们缺乏商业价值,而是因为缺乏构建它们的工程资源。如果人工智能能够以一小部分成本生产软件,那将释放出巨大的潜在需求。那么关键问题就是,这种需求是否会以及何时会饱和。 So to generalize, for each industry, employment hinges on a race between two forces: <br> 因此,总的来说,每个行业的就业都取决于两种力量之间的竞赛: The magnitude and growth of unmet market demand, and <br> *未满足的市场需求的规模和增长,*以及 Whether that demand growth outpaces productivity improvements from automation. <br> 该需求增长是否超过了自动化带来的生产力提升。  Illustrative matrix for different industries <br> 不同行业的说明性矩阵 Different industries will experience different outcomes depending on who’s winning that demand and productivity race. <br> 不同的行业将根据谁在这场需求与生产力的竞赛中获胜而经历不同的结果。 The Bubble: Irrational Exuberance Builds the Future 泡沫:非理性繁荣构建未来 The second debate centers on whether this AI boom is a bubble waiting to burst. <br> 第二个争论的焦点是这次人工智能热潮是否是一个等待破裂的泡沫。 The dotcom boom of the 1990s saw a wave of companies adding “.com” to their name to ride the mania and watch their valuations soar. Companies poured billions into fiber optics and undersea cables - expensive projects only possible because people believed the hype5. All of this eventually burst in spectacular fashion in the dotcom crash in 2000-2001. Infrastructure companies like Cisco briefly became the most valuable in the world only to come tumbling down6. Pets.com served as the poster child of this exuberance raising $82.5 million in its IPO, spending millions on a Super Bowl ad only to collapse nine months later7. <br> 1990年代的互联网泡沫见证了一波公司在名称后加上“.com”以搭上这股狂热的顺风车,并眼睁睁地看着它们的估值飙升。公司投入数十亿美元用于光纤和海底电缆——这些昂贵的项目之所以成为可能,仅仅是因为人们相信这股炒作5。所有这一切最终在2000-2001年的互联网泡沫破裂中以壮观的方式破灭。像思科这样的基础设施公司曾一度成为世界上最有价值的公司,但最终轰然倒塌6。Pets.com成为这种过度繁荣的典型代表,它在首次公开募股中筹集了8250万美元,在超级碗上花费数百万美元做广告,结果九个月后就倒闭了7。 But the dotcom bubble also got several things right. More importantly, it eventually bought us the physical infrastructure that made YouTube, Netflix, and Facebook possible. Sure, companies like Worldcom, NorthPoint, and Global Crossing making these investments went bankrupt, but they also laid the foundation for the future. Although the crash proved the skeptics right in the short term, it proved the optimists were directionally correct in the long term. <br> 但互联网泡沫也在几个方面做对了。更重要的是,它最终为我们带来了使YouTube、Netflix和Facebook成为可能的物理基础设施。当然,像Worldcom、NorthPoint和Global Crossing这些进行这些投资的公司破产了,但它们也为未来奠定了基础。尽管这次崩盘在短期内证明了怀疑论者的正确性,但从长远来看,它证明了乐观主义者在方向上是正确的。 Today’s AI boom shows similar exuberance. Consider the AI startup founded by former OpenAI executive Mira Murati, which raised $2 billion at a $10 billion valuation, the largest seed round in history8. This despite having no product and declining to reveal what it’s building or how it will generate returns. Several AI wrappers have raised millions in seed funding with little to no moat. <br> 今天的人工智能热潮也显示出类似的过度繁荣。以OpenAI前高管米拉·穆拉蒂创立的人工智能初创公司为例,该公司以100亿美元的估值筹集了20亿美元,这是历史上最大的一轮种子融资8。尽管该公司没有产品,并拒绝透露其正在构建什么或如何产生回报。一些AI封装公司在几乎没有护城河的情况下,已筹集了数百万美元的种子资金。 Yet some investments will outlast the hype and will likely help future AI companies even if this is a bubble. For example, the annual capital expenditures of Hyperscalers9 that have more than doubled since ChatGPT’s release - Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon are collectively spending almost half a trillion dollars on data centers, chips, and compute infrastructure. Regardless of which specific companies survive, this infrastructure being built now will create the foundation for our AI future - from inference capacity to the power generation needed to support it. <br> 然而,即使这是一个泡沫,一些投资也将超越炒作,并可能有助于未来的人工智能公司。例如,自ChatGPT发布以来,超大规模云服务商9的年度资本支出增加了一倍多——微软、谷歌、Meta和亚马逊总共在数据中心、芯片和计算基础设施上花费了近五千亿美元。无论哪些具体公司能够幸存下来,现在正在建设的这些基础设施都将为我们的人工智能未来奠定基础——从推理能力到支持它所需的发电能力。  Source: Is AI a bubble, Exponential View, 2025 <br> 来源:《人工智能是泡沫吗》,Exponential View,2025年 The infrastructure investments may have long-term value, but are we already in bubble territory? Azeem Azhar, a tech analyst and investor, provides an excellent practical framework to answer the AI bubble question. He benchmarks today’s AI boom using five gauges: economic strain (investment as a share of GDP), industry strain (capex to revenue ratios), revenue growth trajectories (doubling time), valuation heat (price-to-earnings multiples), and funding quality (the resilience of capital sources). His analysis shows that AI remains in a demand-led boom rather than a bubble, but if two of the five gauges head into red, we will be in bubble territory. <br> 基础设施投资可能具有长期价值,但我们是否已经处于泡沫区域?科技分析师兼投资者阿齐姆·阿扎尔提供了一个出色的实用框架来回答人工智能泡沫问题。他使用五个指标来衡量当今的人工智能热潮:经济压力(投资占GDP的份额)、行业压力(资本支出与收入的比率)、收入增长轨迹(翻倍时间)、估值热度(市盈率)和资金质量(资本来源的弹性)。他的分析表明,人工智能仍处于需求驱动的繁荣期,而非泡沫,但如果五个指标中有两个进入红色区域,我们将进入泡沫区域。 The demand is real. After all OpenAI is one of the fastest-growing companies in history10. But that alone doesn’t prevent bubbles. OpenAI will likely be fine given its product-market fit, but many other AI companies face the same unit economics questions that plagued dotcom companies in the 1990s. Pets.com had millions of users too (a then large portion of internet users), but as the tech axiom goes, you can acquire infinite customers and generate infinite revenue if you sell dollars for 85 cents11. So despite the demand, the pattern may be similar to the 1990s. Expect overbuilding. Expect some spectacular failures. But also expect the infrastructure to outlast the hype cycle and enable things we can’t yet imagine. <br> 需求是真实的。毕竟,OpenAI是历史上增长最快的公司之一10。但这本身并不能阻止泡沫的产生。鉴于其产品与市场的契合度,OpenAI很可能会安然无恙,但许多其他人工智能公司面临着与1990年代困扰互联网公司的同样单位经济学问题。Pets.com也曾拥有数百万用户(当时占互联网用户的很大一部分),但正如科技界的公理所言,如果你以85美分的价格出售美元,你可以获得无限的客户并产生无限的收入11。因此,尽管存在需求,但模式可能与1990年代相似。预计会出现过度建设。预计会出现一些壮观的失败。但也预计基础设施将超越炒作周期,并实现我们目前无法想象的事情。 The Predictably Unpredictable Future 可预测的不可预测未来 So where does this leave us? <br> 那么,这给我们带来了什么启示? We’re early in the AI revolution. We’re at that metaphorical screeching modem phase of the internet era. Just as infrastructure companies poured billions into fiber optics, hyperscalers now pour billions into data centers. Startups add “.ai” to their names like how companies once added “.com” as they seek higher valuations. The hype will cycle through both euphoria and despair. Some predictions will look laughably wrong. Some that seem crazy will prove conservative. <br> 我们正处于人工智能革命的早期。 我们正处于互联网时代那个比喻性的“尖叫调制解调器”阶段。就像基础设施公司曾经将数十亿美元投入光纤一样,超大规模云服务商现在将数十亿美元投入数据中心。初创公司在名称后加上“.ai”,就像过去的公司加上“.com”一样,以寻求更高的估值。炒作将在狂喜和绝望之间循环。一些预测将被证明是可笑的错误。一些看起来疯狂的预测将被证明是保守的。 Different industries will experience different outcomes. Unlike what the Jevons optimists suggest, demand for many things plateaus once human needs are met. Employment outcomes in any industry depend on the magnitude and growth of unmet market demand and whether that demand growth outpaces productivity improvements from automation. <br> 不同行业将经历不同的结果。 与杰文斯乐观主义者的看法不同,一旦人类需求得到满足,对许多事物的需求就会趋于平稳。任何行业的就业结果都取决于未满足的市场需求的规模和增长,以及这种需求增长是否超过了自动化带来的生产力提升。 Cost reduction will unlock market segments. Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor, (in)famously undervalued Uber assuming it would only capture a portion of the existing taxi market12. He missed that making rides dramatically cheaper would expand the market itself as people took Ubers to destinations they’d never have paid taxi prices to reach. AI will similarly enable products and services currently too expensive to build with human intelligence. A restaurant owner might use AI to create custom supply chain software that with human developers, say at $100,000, would never have been built. A non-profit might deploy AI to contest a legal battle that was previously unaffordable. <br> 成本降低将解锁新的市场细分。 金融学教授阿斯瓦特·达莫达兰曾(臭名昭著地)低估了优步的价值,他假设优步只会占领现有出租车市场的一部分12。他没有意识到,大幅降低乘车成本会扩大市场本身,因为人们会乘坐优步前往他们永远不会支付出租车价格的目的地。人工智能同样会催生目前因人力成本过高而无法构建的产品和服务。一个餐馆老板可能会使用人工智能来创建定制的供应链软件,而如果由人类开发人员来做,比如说成本为10万美元,这个项目就永远不会被建立起来。一个非营利组织可能会部署人工智能来参与一场以前负担不起的法律诉讼。 We can predict change, but we can’t predict the details. No one in 1995 predicted we’d date strangers from the internet, ride in their ubers, or sleep in their airbnbs. Or that a job called influencers would become the most sought-after career among young people. Human creativity generates outcomes we can’t forecast with our current mental models. Expect new domains and industries to emerge. AI has already helped us decode more animal communication in the last five years than in the last fifty. Can we predict what jobs a technology that allows us to have full-blown conversations with them will unlock? A job that doesn’t exist today will likely be the most sought-after job in 2050. We can’t name it because it hasn’t been invented yet. <br> 我们可以预测变化,但无法预测细节。 1995年没有人能预测到我们会和网上的陌生人约会,乘坐他们的优步,或者睡在他们的爱彼迎里。或者一个叫做网红的职业会成为年轻人最向往的职业。人类的创造力会产生我们用现有心智模型无法预测的结果。预计会出现新的领域和行业。在过去五年里,人工智能已经帮助我们解码了比过去五十年更多的动物交流。我们能预测一项允许我们与它们进行全面对话的技术会催生出哪些工作吗?一个今天不存在的工作很可能成为2050年最抢手的工作。我们无法说出它的名字,因为它还没有被发明出来。 Job categories will transform. Even as the internet made some jobs obsolete, it also transformed others and created new categories. Expect the same with AI. Karpathy ends with a question: <br> 工作类别将会转变。 即使互联网使一些工作过时,它也改变了其他工作并创造了新的类别。人工智能也将如此。卡帕西以一个问题结尾: About 6 months ago, I was also asked to vote if we will have less or more software engineers in 5 years. Exercise left for the reader. 大约6个月前,我也被问及投票决定5年后软件工程师会变多还是变少。这个问题留给读者思考。 To answer this question, go back to 1995 and ask the same question but with journalists. You might have predicted more journalists because the internet would create more demand by enabling you to reach the whole world. You’d be right for 10 or so years as employment in journalism grew until the early 2000s. But 30 years later, the number of newspapers and the number of journalists both have declined, even though more “journalism” happens than ever. Just not by people we call journalists. Bloggers, influencers, YouTubers, and newsletter writers do the work that traditional journalists used to do13. <br> 要回答这个问题,回到1995年,问同样的问题,但对象是记者。你可能会预测记者会更多,因为互联网能让你接触到全世界,从而创造更多需求。在10年左右的时间里,你是对的,新闻业的就业一直增长到21世纪初。但30年后,报纸数量和记者数量都下降了,尽管“新闻报道”比以往任何时候都多。只是不再由我们称之为记者的人来做。博客作者、网红、YouTuber和时事通讯作者正在做传统记者过去做的工作13。 The same pattern will play out with software engineers. We’ll see more people doing software engineering work and in a decade or so, what “software engineer” means will have transformed. Consider the restaurant owner from earlier who uses AI to create custom inventory software that is useful only for them. They won’t call themselves a software engineer. <br> 同样的模式也将在软件工程师身上上演。我们将看到更多的人从事软件工程工作,大约十年后,“软件工程师”的含义将发生转变。想想前面提到的那个餐馆老板,他使用人工智能来创建只对他自己有用的定制库存软件。他不会称自己为软件工程师。 So just like in 1995, if the AI optimists today predict that within 25 years, we’d prefer news from AI over social media influencers, watch AI-generated characters in place of human actors, find romantic partners through AI matchmakers more than through dating apps (or perhaps use AI romantic partners itself), and flip “don’t trust AI” so completely that we’d rely on AI for life-or-death decisions and trust it to raise our children, most people would find that hard to believe. Even with all the intelligence, both natural and artificial, no one can predict with certainty what our AI future will look like. Not the tech CEOs, not the AI researchers, and certainly not some random guy pontificating on the internet. But whether we get the details right or not, our AI future is loading. <br> 所以,就像1995年一样,如果今天的人工智能乐观主义者预测,在25年内,我们会更喜欢来自人工智能的新闻而不是社交媒体网红,观看人工智能生成的角色而不是人类演员,通过人工智能婚介而不是约会应用寻找伴侣(或者甚至直接使用人工智能伴侣),并且将“不信任人工智能”的观念完全颠覆,以至于我们会在生死攸关的决定上依赖人工智能,并信任它来抚养我们的孩子,大多数人会觉得这难以置信。即使拥有所有的智慧,无论是自然的还是人工的,没有人能确切地预测我们的人工智能未来会是什么样子。不是科技公司的CEO,不是人工智能研究人员,当然也不是某个在网上高谈阔论的无名小卒。但无论我们是否能准确把握细节,我们的人工智能未来正在加载中。 If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it on your socials or with someone who might also find it interesting. Follow me on X.com or LinkedIn to discuss tech and business trends as they happen. <br> 如果你喜欢这篇文章,请考虑在你的社交媒体上分享,或者与可能同样感兴趣的人分享。在X.com或LinkedIn上关注我,一起讨论正在发生的科技和商业趋势。 Footnotes | 脚注 1 Approximately 2,879 websites were established before 1995, expanding to 23,500 by June 1995. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_websites_founded_before_1995 <br>1995年之前大约建立了2879个网站,到1995年6月扩大到23500个。参见 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_websites_founded_before_1995 2 https://www.fastcompany.com/91140068/how-the-internet-went-mainstream-in-1994 3 Historical data from the Industrial Revolution shows that even as aggregate textile employment grew, workers shifted between job types within the industry as some roles became redundant. And correspondingly, some jobs saw wages collapse while others saw increases. For example, domestic hand-loom weavers were displaced by power looms and saw their wages collapse, while self-acting mule spinners (a newly created role) and factory workers saw stable employment and steady compensation growth. Additionally, Britain’s deflationary period (1815-1850) saw food prices fall by half, meaning real purchasing power often rose even when nominal wages declined. Despite all this, the psychological reality was harsh. Even with falling prices, watching your paycheck shrink while neighbors lost jobs and debts grew harder to pay (lower wages but fixed obligations) created real instability regardless of aggregate statistics improvements. Also see Acemoglu & Johnson, 2024. <br>工业革命时期的历史数据显示,即使纺织业总就业人数增长,行业内的工人也在不同工种之间转移,因为一些岗位变得多余。相应地,一些工作的工资崩溃,而另一些则有所增加。例如,家庭手摇织布工被动力织机取代,工资崩溃,而自动走锭纺纱工(一个新创造的岗位)和工厂工人的就业稳定,薪酬稳步增长。此外,英国的通货紧缩时期(1815-1850年)食品价格下降了一半,这意味着即使名义工资下降,实际购买力也常常上升。尽管如此,心理现实是残酷的。即使物价下跌,眼看着自己的薪水减少,邻居失业,债务越来越难偿还(工资降低但债务固定),无论总体统计数据如何改善,都造成了真实的不稳定。另见Acemoglu & Johnson, 2024。 4 Ask any tech product leader about their roadmap planning, and they’ll all universally report far more worthwhile projects than resources to build them, forcing ruthless prioritization to decide what gets built. <br>问任何一位科技产品负责人关于他们的路线图规划,他们都会普遍表示,有价值的项目远多于可用于构建它们的资源,这迫使他们进行无情的优先级排序来决定构建什么。 5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dot-com_bubble#Bubble_in_telecom 6 https://nypost.com/2000/03/28/ciscos-market-cap-tops-microsofts/ 7 https://www.begintoinvest.com/lessons-from-pets-tech-bubble/ 8 https://techcrunch.com/2025/07/15/mira-muratis-thinking-machines-lab-is-worth-12b-in-seed-round/ 9 Hyperscalers are large cloud computing companies like Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon that operate massive data centers and provide the computing infrastructure necessary to train and run AI models at scale. <br>超大规模云服务商是像微软、谷歌、Meta和亚马逊这样的大型云计算公司,它们运营着大规模的数据中心,并提供大规模训练和运行人工智能模型所需的计算基础设施。 10 https://epoch.ai/gradient-updates/openai-is-projecting-unprecedented-revenue-growth 11 https://25iq.com/2016/10/14/a-half-dozen-more-things-ive-learned-from-bill-gurley-about-investing/ 12 Damodaran valued Uber at $6B, assuming a 10% market share of the then $100B taxi market. Uber’s market cap as of October 2025 is $190B. <br>达莫达兰当时假设优步能占据当时1000亿美元出租车市场的10%,将其估值为60亿美元。截至2025年10月,优步的市值为1900亿美元。 13 Job transformation doesn’t guarantee comparable compensation. Much of this new “journalism” or content creation happens for free or at rates far below what traditional news organizations paid, separating the work from stable employment. <br>工作转型并不能保证薪酬相当。许多这种新的“新闻”或内容创作是免费的,或者报酬远低于传统新闻机构的水平,这使得工作与稳定就业脱钩 网闻录 人工智能的拨号上网时代